I’d like to invite you to join me in newsletter-dom.

This will not be your average newsletter.

It will be about creative process and experimentation. About the pursuit of independence and entrepreneurship through writing and digital mixed media.

But, more importantly:

It will be about failure and success, and the efforts, mistakes, and lessons that beget them.

It will be once, at most twice monthly, and you can unsubscribe any time.

I will be reporting from the front-lines of battle while I write and experiment, inscribing little messages on scraps of paper in a language that only you and I can read, delivered by carrier pigeon or by some other covert means.

I hope you’ll join me in The Society of Night Letters.

Charles Barbier de la Serre and his Night Writing

The year was 1806, or possibly 1807, and a dark-haired French artillery officer in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army named Charles Barbier de la Serre had noticed a problem: French soldiers were getting killed at night on the front lines of battle while reading combat messages. In order to see their orders in the darkness, soldiers had to briefly light small oil lamps, revealing them to enemy snipers who would shoot at the glimmers, wounding and killing many soldiers.

Barbier believed these lamp-light deaths to be unnecessary, and he set out to find a solution. Inspired by the ancient Greek Polybius square (a device used for fire signalling and later for cryptography), he encoded each character in the phonetic French alphabet into a series of 12 dots, arranged on a 6x6 grid, which could then be embossed into paper using a combat knife and read by touch, allowing French officers to read combat missives without light. Barbier called this system “Écriture Nocturne,” or “Night Writing” and took it to the French military. Sadly, they had little interest in the invention, believing it was too complicated to be useful.

Not wanting his work to go to waste, Barbier took his Night Writing to the National Institute for the Blind in Paris. There, Louis Braille would encounter it some years later, and, inspired by the idea, develop what is now known as the Braille writing system — a system that has given millions of blind people independence.

I love the premise of Night Writing: a special form of language that reveals what is hidden from sight. I especially love its covert cryptographic roots; the idea of messages and information transmitted between individuals connected by literacy. A secret society of readers.

In our social-media-soaked, virtue-signalling, status-obsessed world, we too often see the polished artefacts of success, the moments of victory, and too infrequently get to see the gritty bits, the experiments, the failures, the false positives, the long nights, and all of the other vicissitudes that precede them. We make miserable, impossible comparisons, because in our algorithm-driven bubbles those who are most successful land at the tops of our news feeds. They become our archetypes. We see the euphoric crest of Everest’s summit, but we don’t see the long journey to base camp, the slow, careful ascension of the mountain’s flank.

That’s what this whole thing is about. Revealing the unseen: sharing creative process, difficulties, speed bumps, moments of inspiration, failures, successes, and everything in-between — conversationally and candidly. Exposing the whole journey and figuring it out aloud. The world needs more of that.

If Barbier created Night Writing, then these are Night Letters.

The ⫶⦙⦙⫶ pictograph in the subject line of each email you will receive is a nod to Barbier, Braille, and every other inventor to who would walk in their footsteps, including you and I.

Footnotes and Credits

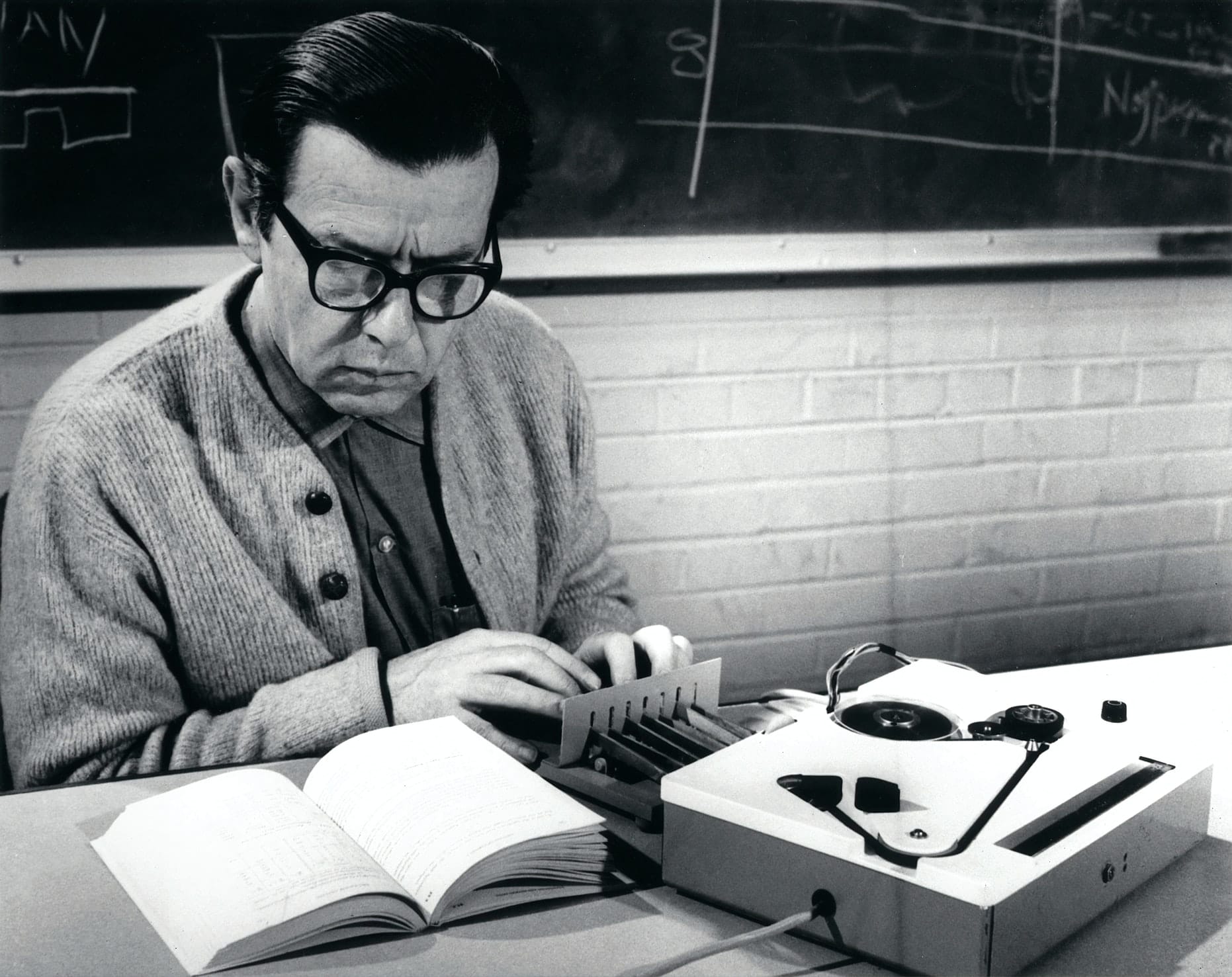

- Feature image courtesy of Science in HD